Roger Ebert

February 27, 1997

The heavyweight title fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Zaire on Oct. 30, 1974--”The Rumble in the Jungle”--is enshrined as one of the great sports events of the century. It was also a cultural and political happening.

Into the capital of Kinshasa flew planeloads of performers for an “African Woodstock,” TV crews, Howard Cosell at the head of an international contingent of sports journalists, celebrity fight groupies like Norman Mailer and George Plimpton, and of course the two principals: Ali, then still controversial because of his decision to be a conscientious objector, and Foreman, now huggable and lovable in TV commercials but then seen as fearsome and forbidding.

“I'm young, I'm handsome, I'm fast, I'm strong, and I can't be beat,” Ali told the press. They didn't believe him. Foreman had destroyed George Frazier, who had defeated Ali. Foreman was younger, bigger and stronger, with a punch so powerful, Mailer recalled, “that after he was finished with a heavy punching bag, it had a depression pounded into it.” Ali was 33 and thought to be over the hill. The odds were 7-1 against him.

The Zaire that they arrived in was a country much in need of foreign currency and image refurbishment. Under the leadership of Mobutu Sese Seko (“the archetype of a closet sadist,” said Mailer), the former Belgian Congo had became a paranoid police state; the new stadium built to showcase the fight was rumored to hold 1,000 political prisoners in cells in its catacombs.

Don King, then at the dawn of his career as a fight promoter, had sold Mobutu on the fight and raised $5 million for each fighter. The “African Woodstock,” featuring such stars as B.B. King, James Brown and Miriam Makeba, was supposed to pay for part of that. For Ali, the fight in Africa was payback time for the hammering he'd taken in the American press for his refusal to fight in Vietnam. For Foreman, it was more complicated. So great was the pro-Ali frenzy, Foreman observed, that when he got off the plane the crowds were surprised to find that he was also a black man. “Why do they hate me so much?” he wondered.

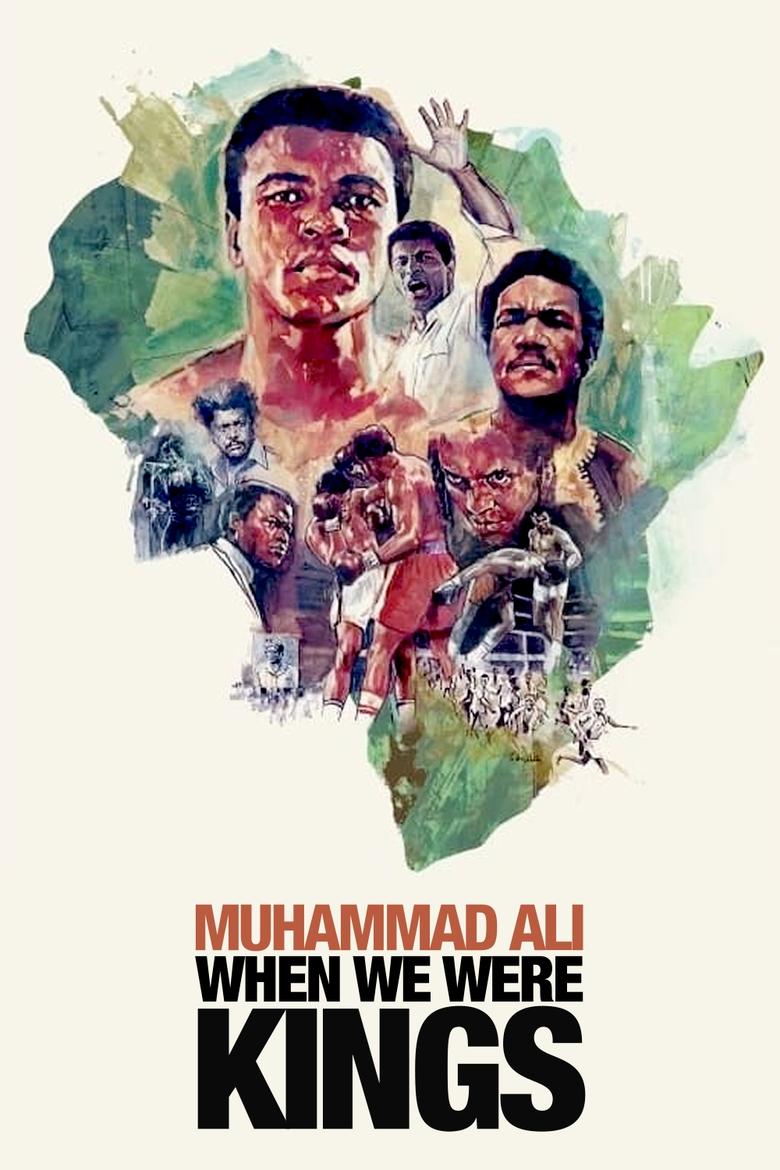

Leon Gast's “When We Were Kings,” which just received an Oscar nomination, is like a time capsule; the original footage has waited all these years to be assembled into a film because of legal and financial difficulties. It is a new documentary of a past event, recapturing the electricity generated by Muhammad Ali in his prime. Spike Lee, who with Mailer and Plimpton provides modern commentary on the 1974 footage, says young people today do not know how famous and important Ali was. He is right. “When I fly on an airplane,” Ali once told me, “I look out of the window and I think, I am the only person that *everyone* down there knows about.” It is not bragging if you are only telling the truth.

The original film apparently started as a concert documentary. Then the fight was delayed because of a cut to Foreman's eye. The concert went ahead as scheduled, and then the fighters, their entourages and the press settled down to wait for the main event. No one really thought Ali had a chance--perhaps not even Ali, who seems reflective and withdrawn in a few private moments, although in public he predicted victory.

How could he have a chance, really? Hadn't he lost his prime years as a fighter after he refused to fight in Vietnam? (“I ain't got no quarrel with the Viet Cong,” he explained.) Wasn't Foreman bigger, faster, stronger, younger? History records Ali's famous strategy, the “Rope-a-Dope” defense, in which he simply outwaited Foreman, absorbing incalculable punishment until, in the eighth round, Foreman was exhausted and Ali exploded with a series of rights to the head, finishing him.

Was this, however, really a strategy at all? “When We Were Kings” gives the impression that Ali got nowhere in the first round and adopted the Rope-a-Dope almost by default. Perhaps he knew, or hoped, that he was in better condition than Foreman, and could outlast him if he simply stayed on his feet. It is certain that hardly anyone in Zaire that night, not even his steadfast supporter Cosell, thought that Ali could win; the upset became an enduring part of his myth.

“When We Were Kings” captures Ali's public persona and private resolve. As heavyweight champion during the Vietnam War, he could easily have arrived at an accommodation with the military, touring bases in lieu of combat duty.

Although he was called a coward and a draft dodger, surely it took more courage to follow the path he chose. And yet it is remarkable how ebullient, how joyful, he remained even after the price he paid; how he is willing to be a clown and a poet as well as a fighter and an activist.

Seeing the film today inspires poignant feelings; we contrast younger Ali with the ailing and aging legend, and reflect that this fight must have contributed to the damage that slowed him down. It is also fascinating to contrast the young Foreman with today's much-loved figure; he, too, has grown and mellowed. When the movie was made all of those developments were still ahead; there is a palpable tension, as the two men step into the ring, that is not lessened because we know the outcome.