The director Mohsen Makhmalbaf made a number of acclaimed films in his native Iran over the Eighties and Nineties, but with the 1998 effort SOKOUT ("Silence") he moved farther afield for his shooting location: Tajikistan, where the locals speak a Persian dialect mostly intelligible to Iranians, but the culture is an exotic mix of Central Asian and Soviet traditions.

Khorshid (Tahmineh Normatova), a blind boy aged around 10, is employed in the workshop of an instrument maker, tuning the instruments. His mother (Goibibi Ziadolahyeva), abandoned by her husband, urges him to work hard, for their landlord is demanding the rent and threatening eviction. Unfortunately, Khorshid is particularly prone to arriving late at work because he is easily distracted from his commute by the sound of music coming from the radio or street musicians. Nadereh (Nadereh Abdelahyeva), the adopted daughter of the instrument maker, tries to keep Khorshid out of trouble. This is a mystical film, by which Khorshid's desire to follow the beauty of music above all else serves as a metaphor for the renunciant's search for God.

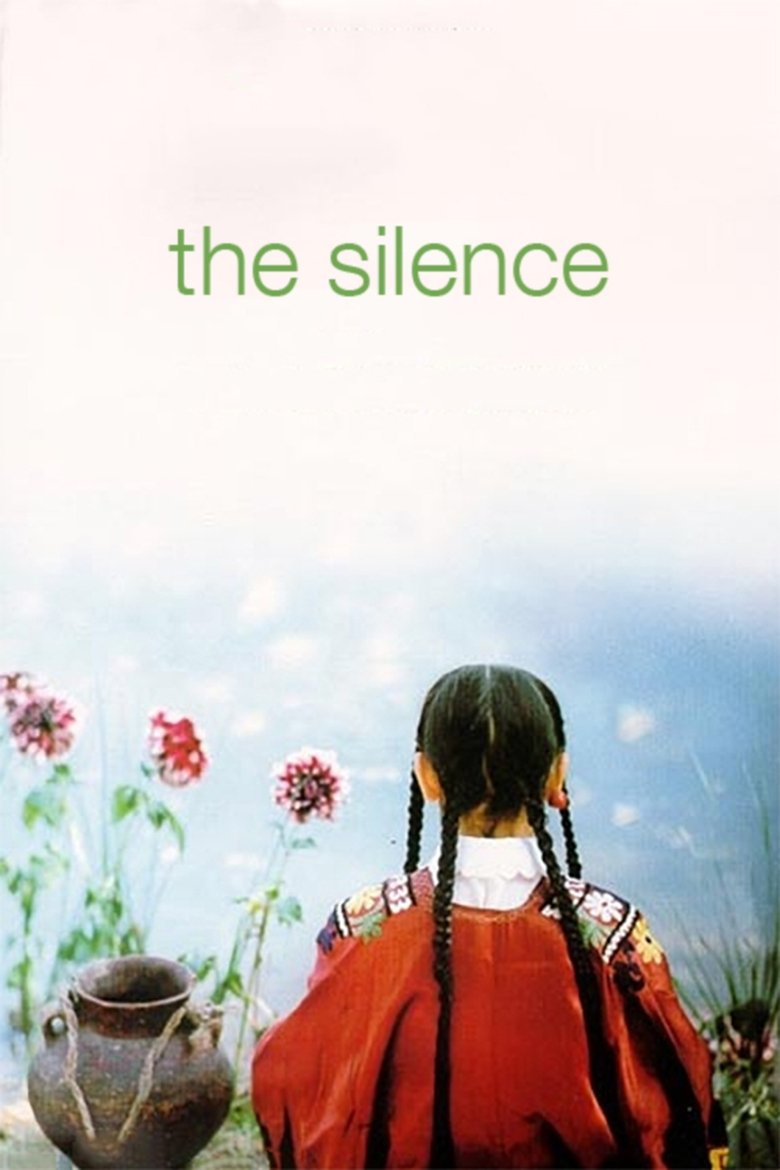

However, that mystical point is made quite subtly, and I suspect most audiences outside the region won't pick up on it. What will strike most foreign viewers is the beautiful imagery and soundtrack. Filming outside Iran in a country with less strict dress codes, Makhmalbaf's camera focuses heavily on female faces and the colourful floral prints of Dushabe's women. In Nadereh and another young cast member he captures that brief moment where girlhood gives way to womanhood. We hear a number of musical instruments from Central Asia, but besides the local folk music the dramatic opening of Beethoven's Fifth figures prominently, tying this exotic locale to a more universal ideal. Things are not entirely rosy, however. The innocence of the children is juxtaposed at a few points with the gritty reality of post-Soviet Tajikistan, now recovering from a bloody civil war and marked by poverty, child labour, and a reborn religious extremism.

The running time is short at 72 minutes, which might disappoint some. Also, Makhmalbaf chose non-professionals to play the roles, and their lines are often delivered somewhat woodenly. However, such wooden dialog may have been desirable to the director, as that slow speech makes the film easier for his native Iranian audience to understand. Still, while not a major masterpiece, this is a visually and musically attractive film and worth watching for anyone wanting a slice of Central Asian drama (or at least one Iranian director's vision of it).