Parallel Mothers

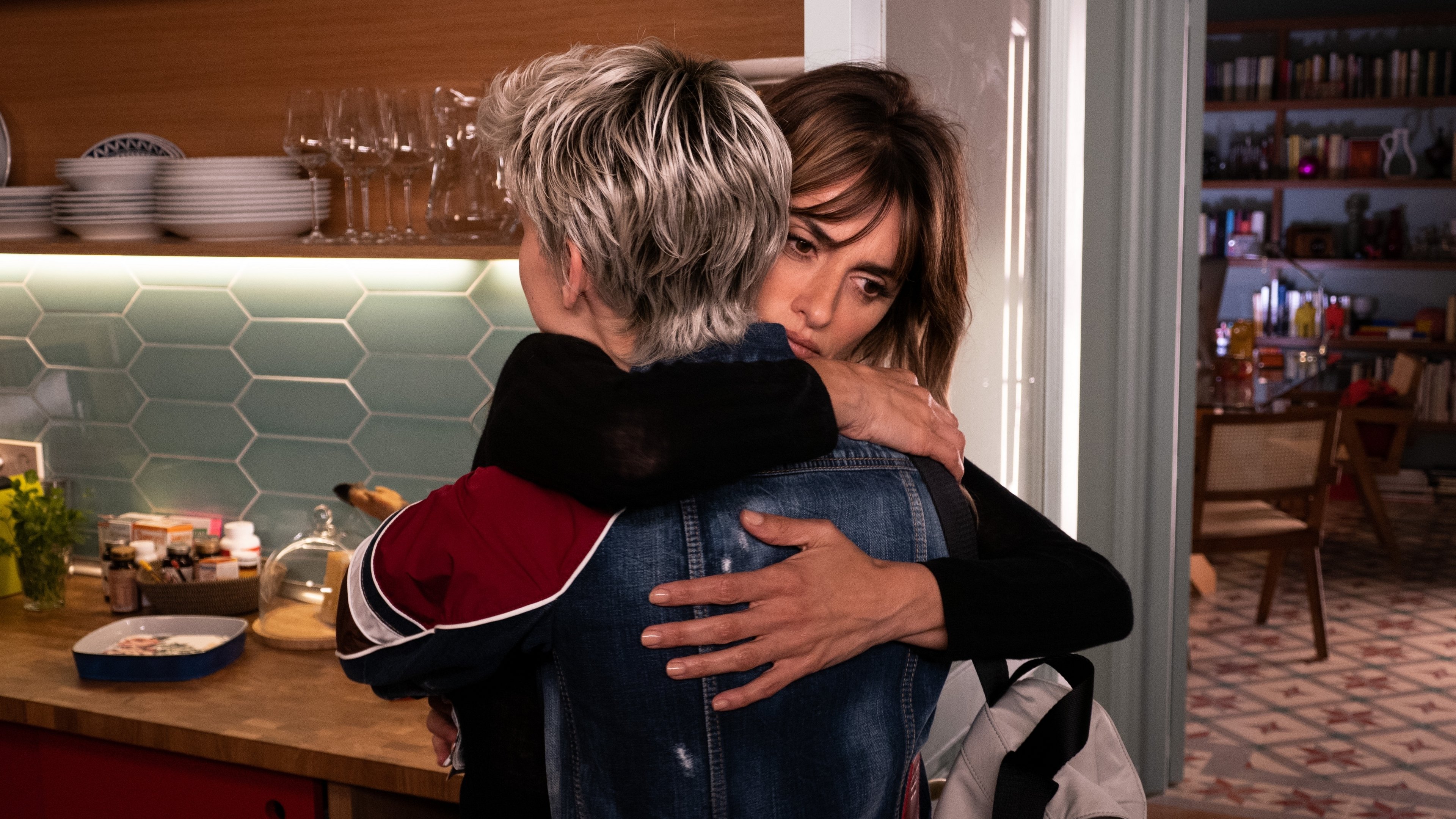

Two unmarried women who have become pregnant by accident and are about to give birth meet in a hospital room: Janis, in her late-thirties, unrepentant and happy; Ana, a teenager, remorseful and frightened.

Manuel São Bento@msbreviews

FULL SPOILER-FREE REVIEW @ https://www.msbreviews.com/movie-reviews/parallel-mothers-spoiler-free-review

"Parallel Mothers holds an unexpectedly shocking narrative about motherhood, featuring two remarkable performances from Penélope Cruz and Milena Smit.

Despite some dull soap-opera moments and a few uninspiring technical attributes, Pedro Almodóvar offers a captivating, genuine, emotionally powerful story that puts the spotlight on imperfect mothers.

Boasting clear direction and a no-nonsense approach, the eponymous parallelism is continuously present throughout the runtime, making this a consistent viewing.

Definitely, a worthy awards contender for Spain."

Rating: B

tmdb28039023@tmdb28039023

Parallel Mothers bespeaks a creative fatigue on the part of writer/director Pedro Almodóvar. Not only is it too similar to his very uneven Julieta from just six years ago, but also rather hard to take seriously – and there is no reason that we should have to or even that he would want us to; the Switched at Birth trope is the stuff of soap operas, and that’s precisely why it would work wonderfully, as that sort of material has in the past, in one of his comedies, but here Almodóvar actually plays it straight, and he goes as far as to throw in a Guerra Civil subplot just so there is no doubt that he means business, and that It Would Be Wrong for us to laugh at this implausible melodrama (though it may be the first melodrama wherein a shot of curtains blowing in the wind actually leads into a lovemaking scene as opposed to standing in for it).

At least Julieta had the benefit of brevity. Conversely, Mothers has some glaring time management issues that result in an unjustifiable 120-minute length. Consider this: Teresa has to tell her daughter Ana that the play she’s starring in is going on a tour of the provinces, as a consequence of which the former is going to leave the latter alone in Madrid with Ana’s newborn baby. A development that ends up having little to no bearing on the plot, and could and should be handled with a couple of throwaway lines of dialogue, is prefaced by a long monologue from Teresa’s play. Why no just cut directly to the scene of Teresa telling Ana the news? (additionally, Almodóvar milks the ‘mystery’ of the baby swap for all it’s worth; the problem is that it isn’t worth squat because we catch on to it ages before the characters do, and whatever suspense the filmmakers hopes to build amounts to zilch since we’re all just waiting for the other shoe to drop).

I’m not saying that the monologue, from a play by García Lorca, doesn’t have some hidden significance; as a matter of fact, I’m completely sure that it has a lot of not-at-all-hidden significance: García Lorca was murdered at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War and his remains have never been found; meanwhile, there is in Mothers some business about the digging of an unmarked mass grave from the first few days of the war that Almodóvar keeps returning to, but where he should have never gone in the first place. On the one hand it draws from cold, hard facts that are fully incompatible with the unlikely events of the far-fetched central narrative, and on the other it is a shameless excuse for a sanctimonious final shot so emotionally manipulative that it needs to be seen to be believed.